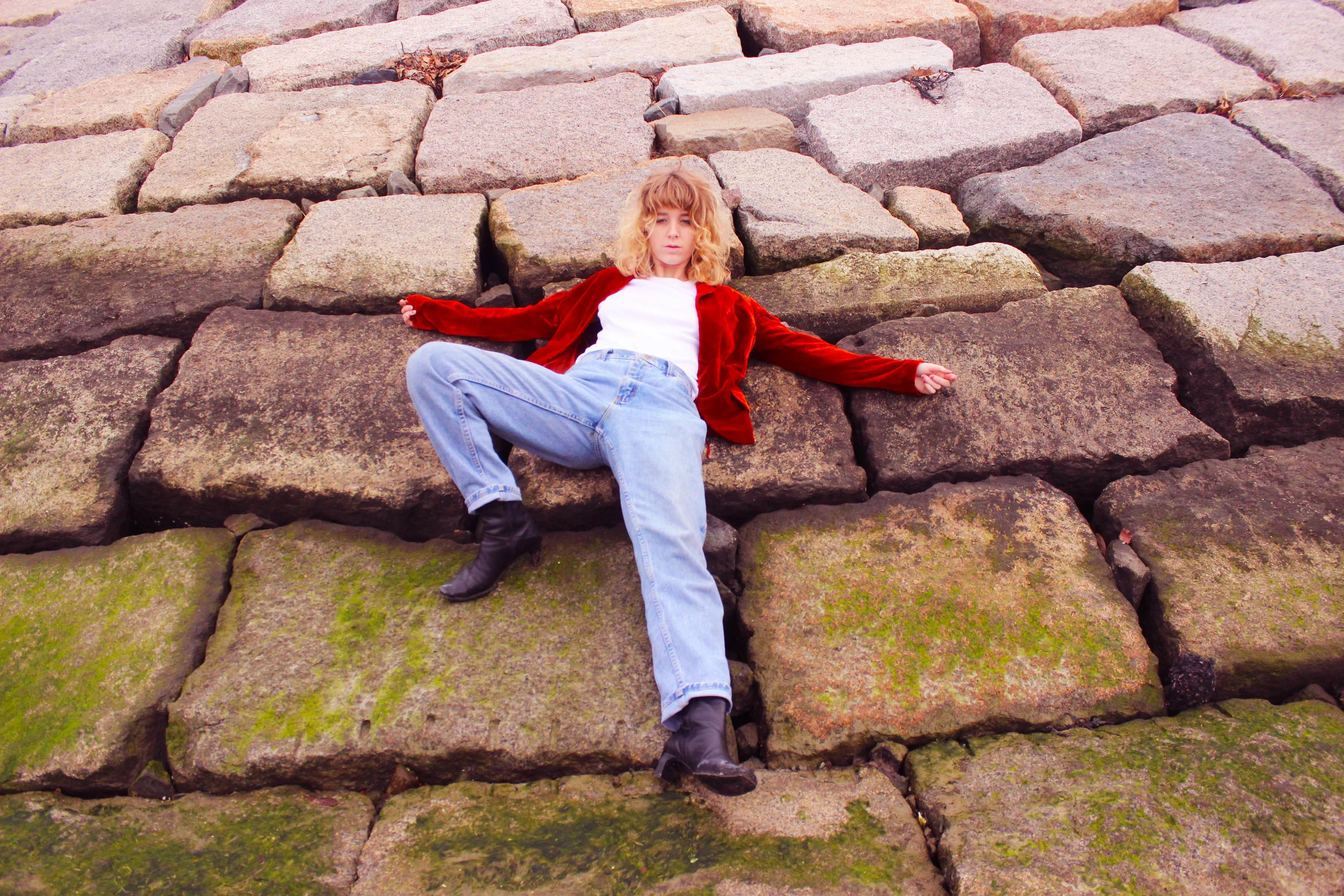

by Sophia Kriegel

Is it selfish to want to leave home? Is that what makes me a child? My mother asks why everyone needs to get out so bad. But how far is my mother from the city that birthed her? (The answer: 1,470.3 miles)

I’ve got a few baby teeth stuck in the pipes, somewhere. My mother has a lock of my hair in a velvet pouch beneath her mother’s pearls. Check the carpet for my fingernail clippings. Check the concrete for my blood. Check the finger paintings and the photo albums and the retainer I forgot to bring to school. What I’m trying to say is, I am a ghost before I am dead.

What I really mean is, we all want to get out. But there’s a stack of half-used journals on the nightstand of my childhood bedroom. And a tiny tooth trapped in the drain. Is it the wanting to go that makes us children? Or is it convincing ourselves that we could ever really be gone?

I came out screaming. We all did. Our mothers in their hospital gowns, pushing as hard as they could, only to be comforted by the sound of our dissatisfaction. Even then, life was never good enough.

I’m sitting at a party filled with kids I’ve known my whole life. We all knew everyone. And yet, nobody knew anyone at all. We all lived different lives, and yet, we all lived the same life. Suburban children squeezed into our mother’s sedans, screaming at the top of our lungs.

The party is at Sarah’s house. I’ve spoken to Sarah a total of three times in the ten years that we’ve gone to school together. That’s the charm of a suburban childhood — the familiarity that has fermented inside each of us for far longer than we would have hoped. Sarah lives a few streets down from my house. The model is the same, though. In this town there are three blueprints for houses, the extent of variety being the color that the shutters are painted. There is a through street — Mallory Drive — the central vein of a city that loops around itself until it is dizzy. Sarah’s house is off of it. So is mine. So is all of ours.

You can only travel up and down the same street so many times before you start blaming it for every sadness in your life.

I’m 11 and walking down Mallory towards Stevenson Ranch Elementary. It is the first day of school and Ella and I are wearing matching outfits. Plaid schoolgirl skirts with matching argyle sweater vests, hers pink and mine blue. My father walks us to the building just as he always has. Each of us holding one of his hands. Now, the city feels as big as his palms. Stretches as wide as his hugs. Wide enough to swallow me whole. He gifts us a sliver of responsibility, shaving off an inch of the city's size. He lets us walk home from school alone.

So, when the time comes for Ella and I to begin the two-block trek, we meet outside the cafeteria. Our feet climbing up Mallory, the same Mallory that we walked that morning, but there is less magic here. The sidewalk is not a red-carpet like my father made it feel like. It is just a sidewalk. I never realized how grey the cement was before.

I’m 16 and take a left off of my street onto Mallory. My father is in the passenger seat giving cautious yet stern directions — this is my first time driving on a residential road. I’m too cocky to be nervous. My father, aware of my narcissism, does his best to humble me in the hopes of making it home in one piece. I’m cruising down the street at a crisp speed of 34 miles per hour, the most momentum my hands have mustered in their weathered life.

“Make a right here,” my father says.

I turn my head. I hear him late and make a delayed right turn off of Mallory. I almost hit a pedestrian, a moving vehicle, and a parked car. And now I’m sobbing. My father is yelling. My hands are shaking. It’s not my fault. If only the street went on for longer. If only the road told me to turn quicker. My dad drives home. I don’t say anything the whole ride; I just look out the window, past my elementary school and the park and the pavement, tears staining my cheeks, red with adolescent resentment.

I’m 18 and in the passenger seat of my sister’s car while she drives up Mallory. It is 2 a.m. and we’re on our way home from a party. I drank too much. I did it on purpose. But now, Ella and I are fighting. Screaming at one another, something about how we can’t wait to be far away from from this town and these people and each other. I can’t take it anymore. I unbuckle my seatbelt and reach for the door handle.

“I’ll jump. I’ll do it,” I tell her.

The child lock stops me.

I wonder if that street would have caught me. If it would have wrapped me in its arms and warded off any severe injuries. Or if it would have let me break my legs. Punishment for my passionate rage towards it. The time I yelled that I couldn’t stand this stupid town with its stupid streets and suffocating mentalities. It heard me. It knows I hate it. We all hate it. How can we not? The pavement on which we scraped our knees, fell flat on our faces, ran from home, cursed our lives. Begged to leave.

We’ve taught ourselves to resent the roads we learned to walk on. Situate our anger at our mothers and our school teachers and the cashier at the supermarket who used to hand us lollipops when we were kids, but now, doesn’t even recognize us beneath our angst. We are angry. We are so angry at the suburb for stripping us of some sort of dreamlike city life where everything is beautiful because we do not know it.

I’m 19 and driving up Mallory on my way home from the airport. It’s my first time back since moving across the country. I realize that the suburb had sunk its teeth into my neck and left an imprint I will never be able to shake. I want, desperately, to feel like a stranger again. I want to prove to myself that we are not one — that suburb and I. So, as I drive up the street I’ve driven up one million times — the pathway home where all the homes look the same and all the children hate their parents too — I close my eyes. I want to crash. I want to prove that I do not know the twists of this town like the back of my hand. That I could not navigate this monotony with my eyes closed. That I could leave and forget and be more than Mallory Drive.

I don’t crash.

After months and months of being away, I could drive up that hill, eyes closed, in the pitch black, all the way home. I’m angry because I hate this town. But I think I am this town. And I always will be.